In today’s second reading from the Letter to the Hebrews there is another passage reminding us that when we gather to celebrate the Eucharist, we gather with the saints and angels in heaven, called the “firstborn enrolled in heaven” (Hb 12:23). [1] This weekend the Church celebrates the feastday of St. Augustine (August 28) and also his mother St. Monica (August 27).

Augustine was born in A.D. 354 in the town of Tagaste, in a north African province of the Roman Empire, in modern day Algeria. One of three children, he was raised by a devout Catholic mother, St. Monica, and an unbaptized pagan father Patricius. Monica was unable to baptize her children because of the objections of Patricius, but she tried to raise them in the Christian faith.

Augustine’s family life was not easy. His parents married very young, his father was unfaithful to his marriage, had a violent temper, and drank heavily. Monica struggled to keep her family together, and tried to respect and love her husband despite a lot of pain and disappointment. Other women were impressed by her gentle approach, and perseverance.

As a young adult, Augustine studied to become a teacher in the city of Carthage. He began living with a young woman and together they had a son whom he named Adeodatus, “Gift of God.” He also joined a religious sect of “Manicheans,” following a Persian mystic who taught the strict dualism and struggle between spirit which is good, and matter which is evil. For Augustine, this was a deeply personal struggle that lasted many years. He was strongly attracted to the ideals of a purely spiritual life, but struggled greatly with the selfish desires of the flesh.

It was during this time at Carthage that Augustine’s father was baptized as a Catholic, shortly before he died. In pursuit of his academic career, Augustine left north Africa for Italy where he established a school first in Rome, and then later in Milan, which by that time had become the new capitol and residence of the western Roman emperor. His mother Monica joined him in Milan.

In Milan Augustine continued to deepen his studies, and found a new home with a circle of scholarly friends, many of whom were Christian. He also began to attend the church services at the cathedral, not because he was interested in Christianity, but because the bishop of Milan was a brilliant intellectual and famous orator, whose rhetorical skills were highly praised. God arranged for one great intellectual, St. Augustine, to meet another spiritual giant, St. Ambrose.

St. Ambrose became bishop of Milan in 374 at the age of 34, in unusual circumstances. The church was in the midst of a struggle with the Arian heresy, and when the Arian bishop of Milan died in 374 the city devolved into chaos in the struggle for a successor. Ambrose was a respected lawyer who worked in the civil government as an administrator, and the emperor Valentinian appointed him to mediate the conflict with the regional bishops, and help them choose the next successor for Milan. In the cathedral, Ambrose began a great discourse on peace and harmony, but was interrupted by a child who kept crying, “Ambrose, bishop.” The gathered bishops took up the chant, and unanimously elected Ambrose as the new bishop.

Only one problem: Ambrose was not clergy, nor was he even baptized. He was a believer, but still a catechumen in what we call “RCIA” today. Within 8 days, he was baptized, fully initiated, and ordained a bishop! And he became one of the best bishops the Church ever had. He defended the Church from the Arian political wing, which even sent armed police to seize his cathedral. He excommunicated the emperor and made him do public penance. He codified and expanded the liturgy and rituals of the Church, composing many of the prayers himself. The “Ambrosian Rite” of the Catholic Church, somewhat distinct from our regular “Latin Rite” we are familiar with, continues to be used the diocese of Milan to this day. His theological treatises, defense of the orthodox faith, commentaries on Scripture, homilies, and other writings are extensive. Ambrose personally preached the Word of God, daily, in his cathedral, attracting consistent large crowds. Regularly among them was this new arrival from North Africa, and his devout mother.

Augustine had long ago written off the Christian religion, and was especially critical of many parts of the Old Testament. But he had also abandoned the Manicheans after he found their teachings to be without substance. And whereas he first came to hear Ambrose because of his eloquence, he began to understand the prophecies of the Old Testament as Ambrose explained them, and soon started to appreciate the fullness of Christian truth, as many of his intellectual friends already had. The first big hurdle in his conversion was overcome, and Augustine became a believer.

God created man with intellect, which seeks truth, and Augustine had come to the Truth. But God also created man with will, which seeks the good, and here Augustine still struggled. He knew the right thing to do, but was weak, and not ready to go there. One of his big struggles was chastity. You can’t be baptized if you are living in sin with someone, outside of marriage. Interestingly, even though Augustine lived with his girlfriend for fifteen years, he never married her. Monica could see the problem clearly: he didn’t want to marry her, she was not of the same economic class. Augustine wanted her for a concubine. Though he loved her and cared for her, he also recognized that he was selfishly using this relationship in a fleshly way, and not for the noble purpose of marriage, where a man and his wife take their place as equals in the community. Augustine prayed, “Lord, give me chastity, but not yet.”[2] He knew what he needed to do, but couldn’t do it.

This is where grace is needed. We cannot save ourselves, or overcome our sins by our own power, and God has to make us learn the hard lessons of human weakness in order that we can finally be humble enough to trust Him. For Augustine, the day came in late August of 386, when he was 31. While reading and reflecting on a great spiritual work in the patio of his house, the “Life of St. Anthony of the Desert” (written by another great saint of the Church, the bishop St. Athanasius of Alexandria), and struggling greatly with the turmoil inside himself, Augustine all of a sudden heard the voice of a little child outside the wall crying out, tolle lege, “take up, read.” Maybe it was the same angel who cried out in the cathedral for St. Ambrose. Augustine picked up a book of St. Paul’s letters which he had nearby, randomly opened it, and read the first passage that he saw. It was Romans 13:12-14:

“The night is far gone, the day is at hand. Let us then cast off the works of darkness and put on the armor of light; let us conduct ourselves becomingly as in the day, not in reveling and drunkenness, not in debauchery and licentiousness, not in quarreling and jealousy. But put on the Lord Jesus Christ, and make no provision for the flesh, to gratify its desires.”

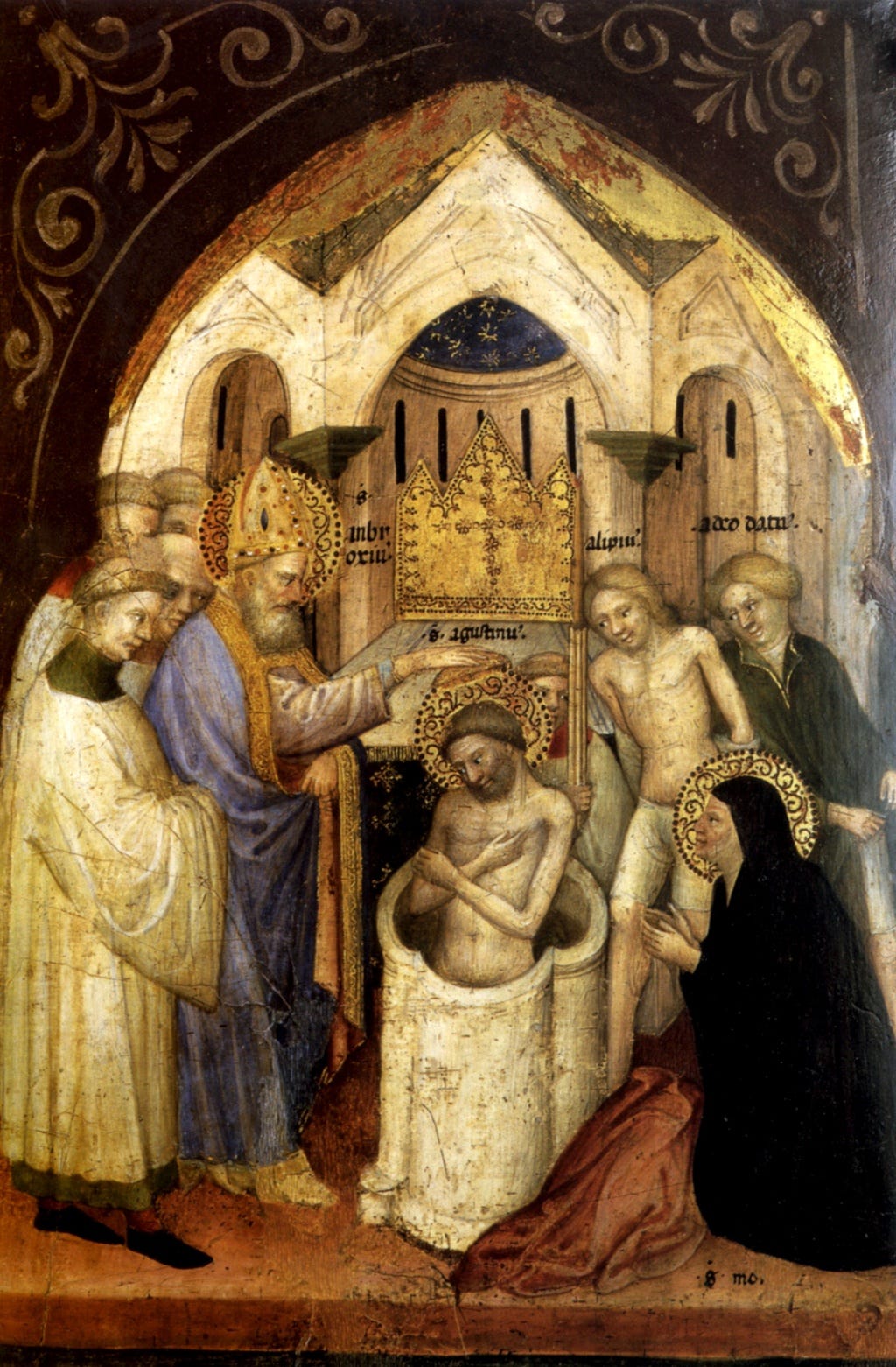

Writing later in his Confessions, he described his experience of instantly being overwhelmed with the peace of God. In that moment he was healed. The following year he was baptized at the Easter Vigil by Bishop Ambrose, together with his son Adeodatus. Within a year his mother Monica died, satisfied that she had completed her mission to see her family all Catholic.

St. Augustine resolved to live a celibate life, and dedicate himself to prayer, study, and writing. He returned to north Africa to the town of Hippo, not far from where he grew up. Here he began to live in community with a band of brothers, and established a community rule which now serves as the basis for most of the active apostolic religious communities in the Catholic Church. He was ordained a priest, and soon became the bishop of Hippo. From his community, men became bishops of all the surrounding churches.

St. Augustine, like St. Ambrose became one of the greatest Church fathers and doctors in the West, and his treatises and works served as the foundation for theology into the middle ages. Supporting Pope St. Damasus I, he was instrumental in codifying the official books of the Bible, in articulating the Church’s doctrine of the Holy Trinity, and explaining the role of grace and free will in Christian life. When he died in 430, the Roman Empire in the West was falling to the invasions of Barbarians, reaching his own town as he lay on his deathbed. His library survived the sacking of Hippo, and served as a light for the dark ages to come.

St. Augustine is one of the greatest saints in the Church, yet this greatness is found in his humility that allowed him to surrender completely to God’s grace, and be loved completely by God:

You have made us for yourself, O Lord, and our heart is restless until it finds its rest in you. (Confessions, 1,1.5)

Late have I loved you, O Beauty ever ancient, ever new, late have I loved you! You were within me, but I was outside, and it was there that I searched for you. In my unloveliness I plunged into the lovely things which you created. You were with me, but I was not with you. Created things kept me from you; yet if they had not been in you they would have not been at all. You called, you shouted, and you broke through my deafness. You flashed, you shone, and you dispelled my blindness. You breathed your fragrance on me; I drew in breath and now I pant for you. I have tasted you, now I hunger and thirst for more. You touched me, and I burned for your peace. (Confessions, 10.27.38)

[1] “You have approached Mount Zion and the city of the living God, the heavenly Jerusalem, and countless angels in festal gathering, and the assembly of the firstborn enrolled in heaven” (Hb 12:22-23).

[2] Confessions, 8:7.17