St. Gregory the Great was born in Rome in 540, and was pope from 590 to 604. He grew up a “saint among saints”: His mother Silvia is canonized, as are his two aunts, Tarsilla and Aemiliana, the sisters of his father Gordianus. Gregory grew up at a time when the Western Roman Empire had collapsed, and Rome was sacked twice in his youth by Goths from the north. He was the prefect (governor) of Rome, but at age 34 left everything to become a monk, donating his father’s entire estate for the founding of seven additional monasteries, including the monastery of St. Andrew in Rome where he lived.

St. Gregory was the first monk to become a pope, and as pope he would be a great promoter of Benedictine monasticism throughout the Catholic Church. St. Benedict of Nursia (480-543) was the founder of western monasticism, who died at the monastery of Monte Cassino near Rome when Gregory was a young boy of three. The monastic rule which St. Benedict composed for his monks establishes a life of prayer and work, “Ora et Labora.” Each monastery is designed to be a stable, self-sufficient community of Christian brothers (or sisters), under the governance of an abbott (or abbess), who live in fraternal charity, and who not only provide for their own needs but for those of the community around them.

First and foremost, a Benedictine monastery is a place of prayer and worship, built around a central church where the monks gather seven times a day to chant the Liturgy of the Hours and celebrate Mass. Additional buildings are for communal meals (refectory), personal cells (monks’ individual rooms), library, scriptorium, infirmatory, workshops and factories, and houses for guests. Hospitality for travelers and care of the sick and poor are always a priority. Finally, monasteries have gardens and extensive fields for agriculture and farming. At a time when the Roman civilization and technical expertise collapsed, monasteries often remained as the only reliable centers for education, agriculture and industry, medical care, communication, safety, and social order, a “light” shining in a “dark age.”

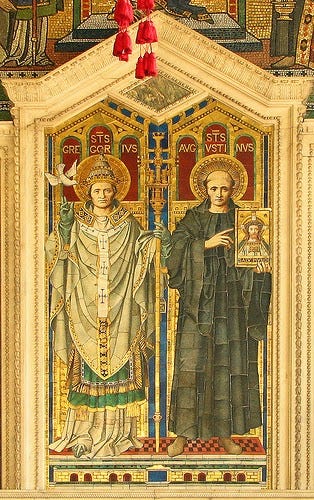

Gregory was first called away from the peace of the monastery in 578, when Pope Pelagius II sent him as ambassador to request help from the eastern Byzantine emperor in Constantinople. This six-year mission was a failure, and no help would come from the east. It taught Gregory he would have to be resilient. Returning as Abbott of his beloved monastery of St. Andrew, he devoted himself to the preaching of Scripture, and extensive writing. Together with St. Augustine, St. Ambrose, and St. Jerome, St. Gregory the Great is numbered as one of the four great Latin fathers of the Church.

It is also during this time that he famously encountered the fair-skinned youths from a distant land in the Roman Forum. Discovering that they were “Angles,” he petitioned the pope to be sent as a missionary to these noble pagans, but the people of Rome would not permit him to leave. Because of his background and natural gifts, Gregory had become indispensible to the pope and city of Rome.

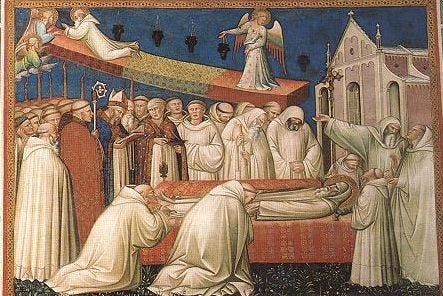

St. Gregory lived in a calamitous time, where the great horsemen of the apocalypse (Rv 6) ravaged Italy one after the other: destructive barbaric invasions, catastrophic natural disasters (such as the great flood of 589), leading to devastating plagues and famine, and finally to death beyond the ability to bury all the bodies. When Pope Pelagius died in 590, Gregory was unanimously elected his successor, and he was consecrated that year on September 3, later to become his feastday. Despite ill health, the 14 years of St. Gregory’s pontificate have left an indelible impact on the Church.

1) He organized the entire machinery of the church, especially the monasteries, to address the widespread famine and refugee crisis. This model would help the church address all the various challenges of the upcoming “Dark Ages” throughout Europe, providing a foundation for Charlemagne to reestablish a new “Holy Roman Empire” in 800 A.D.

2) He codified and expanded the liturgical and devotional rites of the Church. Through the influence of his Benedictine monastic background, the Mass attained a form that remained in use throughout the Middle Ages and up to Vatican II. For instance, it was St. Gregory who added the Lord’s Prayer to the ritual of the Mass, and composed many of the other prayers. He is also credited with setting forth the distinctive manner of reciting the sacred Latin prayers, known as “Gregorian Chant.”

3) He personally modeled and set forth the disciplined manner by which clergy in the Latin Church are to live and lead the faithful: simplicity of life, celibacy, prayer, and service to others. He also established the proper roles and relationships between monks, and the “regular clergy” of a diocese.

4) He advanced the international role and authority of the papacy, regularly intervening to settle disputes among bishops of various regions, appointing bishops, and advancing relations with peoples and nations, including the eastern Byzantines, and western Lombards and Franks.

As pope, Gregory was able to fulfill his desire of evangelizing the people of “Angle-land,” by sending a contingent of monks to them in 595 from his beloved monastery of St. Andrew. The leader of this group, St. Augustine,[1] established the first monastery and diocese in England at Canterbury. From these beginnings, many future monasteries would be established from England throughout the Germanic territories, leading to the complete evangelization of the “Barbarians” who ravaged the Roman Empire in Gregory’s day, and paving the way for Charlemagne’s coronation as first “Holy Roman Emperor” of the West.

In art, St. Gregory the Great is typically depicted in full papal regalia with a dove at his lips. His secretary witnessed this miracle of the Holy Spirit directly inspiring the words of the great saint when he would dictate his homilies.

In today’s Gospel Jesus said his followers must build their discipleship on the proper foundation: “anyone of you who does not renounce all his possessions cannot be my disciple” (Lk 14:33). Gregory perfectly modeled this by giving his large family estate to the church for the work of evangelization, and to help people in great need. Gregory was like the resourceful builder and general described by Jesus, whose work set the church’s course for centuries.

And just as St. Paul’s letter to Philemon set forth the basis by which the Church overcome the widespread practice of slavery in the ancient world (“[I send Onesimus back to you] no longer as a slave but more than a slave, a brother” – Phlm 16), so Gregory immediately recognized the English slaves in the forum as future brothers to be incorporated into the family of the Catholic Church.

Today we live in a world where civilization is also in a state of collapse. St. Gregory’s life challenges us to ask whether the church is prepared today to be able to step into the moral void and be the light of nations. Do we have what it takes to be the resourceful builder of a new Kingdom (Lk 14:30)? Are we able to fight the upcoming battles against the forces of darkness and chaos (Lk 14:31)?

[1] St. Augustine of Canterbury (d. 604), not to be confused with St. Augustine of Hippo (354-430)