In this final Sunday before the Solemnity of All Saints, I would like to highlight the example of one of the Apostles. Unfortunately, not much is known about most of the Apostles beyond what we read in the Gospels, and a few historical references and traditions. After writing his Gospel St. Luke began to compile the “Acts of the Apostles” but did not even complete his account of St. Paul the Apostle before the work was interrupted, likely by his martyrdom.

The Apostles are the foundation of the Church, personally chosen and sent by the Lord to preach the Gospel in his name and power. After the Resurrection they went to the ends of the earth, from Spain to India, and from the northern limits of the Roman Empire to Africa. They preached Jesus from their personal experience and memory, recounting again and again his teachings and the stories of his miracles, which began to be compiled in the Gospels after many years.

The Apostle I am choosing for this Sunday is important to our church due to his statue, and also due to his feast day which was on Friday, October 28: St. Jude. St. Jude is also the author of the very brief “Letter of Jude,” located just before the Book of Revelation, and he is always listed toward the end of the apostles. Today’s Gospel provides an excellent introduction to an important story about St. Jude.

There was a rich man in Jericho who had heard of Jesus and climbed a sycamore tree to see him as he passed by in the crowd. Jesus was famous for his miracles, and many people wanted to see him, even those who lived in distant lands. With Zacchaeus, Jesus was able to bring salvation to his house by his own immediate presence. But for people in other lands, Jesus brought salvation by coming to them through the apostles of the Church.

One such man, who like Zacchaeus wanted to see Jesus, was Abgar the king of Edessa. He was very ill and could not travel. Hearing that Jesus was a great physician who could heal without herbs or medicine, Abgar wrote a letter to Jesus asking him to come and bring healing to him in his house in Edessa. Jesus was approaching his passion and death and could not go, but he promised to send a disciple. After the Resurrection a disciple did indeed go to the king, taking with him an image of the Lord, and the king was healed. Like Zaccahaeus, “salvation came to his house.” St. Abgar was baptized, the first Christian king, and together with him his people.[1]

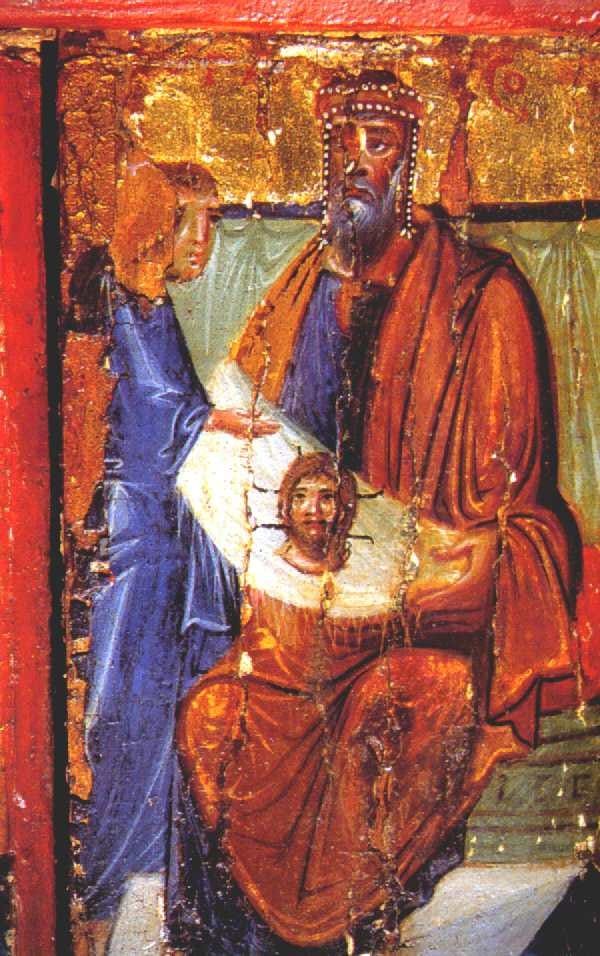

The disciple who brought the image to king Abgar was named Thaddeus (or “Addai”), which is the alternate name of the apostle Jude.[2] St. Jude is therefore often depicted carrying an image of Jesus. In later centuries this image of Jesus’ face, known as the “Mandylion of Edessa,” was venerated publicly in the Christian city of Edessa and became famous world-wide. All early icons of Jesus copied this image, giving us the standard portrait of Jesus which is considered to be his likeness.[3] When Muslim armies advanced on Edessa in the early 600s, the image was transported to Constantinople, where it remained until the Crusader armies sacked the city in 1204 and stole it.

It is widely believed that the image of Jesus which St. Jude Thaddeus brought to King Abgar in Edessa was the burial shroud of Jesus, which has a miraculous image on it, and this shroud was folded and framed in a box such that only the face was displayed.[4] St. Jude was a brother – i.e. close relative – of Jesus (Mt 13:55, Mk 6:3).[5] Perhaps this is what allowed him to take possession of the burial shroud after the Lord’s Resurrection.

We venerate St. Jude especially for assistance in hopeless or desperate situations, but most importantly, he teaches us what it means to be an Apostle of Christ. Not only bishops and priests by Holy Orders, but all the Christian faithful by means of Confirmation have a share in the apostolic ministry, which is to bring Christ to others by carrying his image within and showing it forth through preaching. Confirmation “seals” the image of Christ indelibly into the soul, enabling us to imitate St. Jude and all the saints, in whose lives Christ is revealed.

[1] Bishop Eusebius of Caesarea (265-339) is an early Church historian who gives the account of the conversion of King Abgar by Addai/Thaddeus, and the origins of the image of Edessa (Historia Ecclesiastica, I, xiii).

[2] There is some scholarly debate with regard to the identity of St. Jude.

In St. Luke’s list of the twelve apostles (Lk 6:16 and Acts 1:13), and also in St. John (14:22) he is named “Jude” or “Judas” “of” James (likely meaning brother of James). In the Gospels of St. Matthew and St. Mark on the other hand (Mt 10:3, Mk 3:18), he is called “Thaddeus.” They are certainly the same apostle, and various reasons are given for the two names. First, it was common practice to have a nickname or a surname, such as also occurred with “Simon Peter,” or “Nathaniel Bartholomew.” Secondly, Christians may have focused on the alternate name for Jude to distinguish him clearly from Judas Iscariot, who betrayed the Lord.

In Eusebius’ account of King Abgar, the disciple is called “Addai,” which is likely a Syriac or Armenian variation of “Thaddeus.”

St. Thaddeus of Edessa is considered one of the “Seventy Two” disciples whom Jesus had sent out previously on missionary activity (Lk 10:1-20). In the Gospel of St. Luke, the “Seventy” (or “Seventy Two”) are distinguished from the “Twelve” (cf. Mt 10:1-5; Mk 3:13-19; Mk 6:7-13; Lk 6:12-16; Lk 9:1-6; versus Lk 10:1-20). However, there is no reason to suppose that Jesus did not appoint the “twelve” apostles from among those who were also in the group of “seventy two.”

[3] The famous icon of “Christ Pantocrator” in the Monastery of St. Catherine at Mt. Sinai, dates from the 6th century and is one of the oldest icons showing this tradition of depicting Jesus in the same way. It is extremely interesting and significant that the early church documented the existence of an actual image of Christ, which was known to the apostles, and subsequently imitated and copied.

[4] While in Constantinople, the Mandylion was unfolded and displayed in its full 14-foot length, and copied many times in liturgical books throughout the west by pilgrims who visited and saw it in Constantinople. After disappearing from Constantinople in 1204, the cloth reappeared in Lirey, France, in 1353 in the possession of Templar Knight descendants, and was transferred to Chambery before finding its present home in the cathedral of Turin, Italy. The Shroud contains various actual blood stains from the wounds of Christ, but it also contains a mysterious and undistorted photographic image of the entire length of Christ’s body, front and back. It also has various tears, holes, burns, and fold marks accumulated through its 2000 year history, including the marks showing exactly how it was folded while in the framed box at Edessa. Forensic analysis has also shown that the shroud has localized pollen on it from the regions of Jerusalem, Edessa, Constantinople, and France.

[5] In biblical times, “Brother” is a broad term meaning any close relative. The early apostolic father Papias of Hierapolis (70-163), considers Jude to be the brother of the apostle James the Lesser, son of Mary and Cleophas (Exposition of the Sayings of the Lord, Fragment X). James the Lesser (distinguished from James son of Zebedee) was the first bishop of the Church in Jerusalem after the Resurrection, and presided at the council held there (described in Acts 15). Cleophas or Alpheus (cf. Mt 10:3, Mk 3:18; also Mt 27:56; Mk 15:40), in turn is believed to be the brother of Jesus’ father Joseph, which would make the apostles Jude and James the Lesser the first cousins of Jesus.

Fantastic Father, thank you for your work, I’ll be looking forward to these!