Jesus tells the Parable of the Good Samaritan in order to illustrate the “Great Commandment,” which is to “love God with all your heart, soul, mind and strength,” and “your neighbor as yourself” (Lk 10:27). Jesus clarifies for the scholar what he also taught in the Sermon on the Mount (cf. Mt 5:43-48), that “neighbor” is to be understood in a catholic or universal sense. We are to love everyone, even including one’s enemies. Thus Jesus uses the example of an enemy of Jews, a Samaritan, to illustrate the teaching.

The parable not only illustrates the “Great Commandment,” it also illustrates the “New Commandment” of Jesus, which is to “love one another as I have loved you” (Jn 13:34). By his Incarnation, Jesus joins together the vertical dimension of love of God and the horinzontal dimension of love of neighbor. In him, divine love and human love are identical.

A man fell victim to robbers as he went down from Jerusalem to Jericho. Jerusalem is the Holy City of God, set high upon Mt. Zion in the middle of the Promised Land. Jericho is the City of Man, located far below in the Jordan valley, near the Dead Sea. Israel’s journey back to God begins at Jericho, and ends in Jerusalem. That ascent is the final stage of the pilgrim’s route to the great festivals, it is the path Jesus followed when he came to Jerusalem for Passover. The descent from Jerusalem to Jericho, on the other hand, represents the fall of man, who lost heaven as he chose to cling to himself in this world.

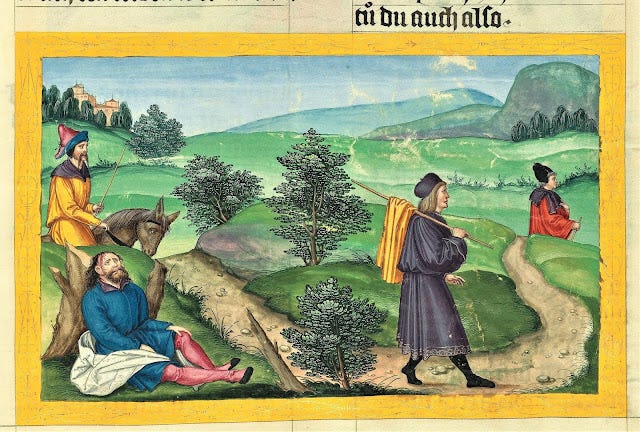

The robber who brought about this fall is the devil, who injured and stripped the man and left him half dead. By his sin man lost the grace and friendship of God, which left him injured in his nature, naked and full of guilt. The injuries of Original Sin leave man “half-dead,” alive for a time but destined to be cut off from God. Man cannot help (save) himself, and he cannot return to Jerusalem.

This man, therefore, is Adam, who represents all mankind, not just the Jews. The first priest likely represents the patriarchal priesthood and covenant with Abraham, while the Levite represents the Law and covenant instituted by Moses, neither of which can heal or “save” man. They are only preparations that look forward to the One who will come and save his people. These covenants therefore pass on, and then comes the savior.

Jesus deliberately depicts himself as a Samaritan, because his origin is “outside.” He comes both for the Jews, as “Son of Abraham, Son of David,” but also for the Gentiles and all mankind, as “Son of Man.” When he saw the wounded man, the Samaritan was moved with compassion. Even though man had sinned, God’s heart was moved with compassion and love. “God so loved the world that he gave His only Son…” (Jn 3:16). Though we could do nothing to help ourselves in our condition, God came to help us. “Love consists in this, not that we have loved God, but that He has loved us” (1Jn 4:10). God descends from heaven to earth, in a sense following man down the same path of his fall, going to death itself, so that He might save and restore man to his former dignity: “For us men and our salvation he came down from heaven…”

The Samaritan poured oil and wine in the man’s wounds. Unlike the priest and levite, who are unable to help the man, Christ comes with heavenly blessings to heal and restore. In the oil is reference to the sacraments of Baptism, Confirmation, and Anointing; in the wine is reference to the sacrament of the Eucharist.

He lifted him up on his own animal… The beast of burden was likely a donkey, calling to mind Jesus’ entrance into Jerusalem for the Passion. What Jesus does, beginning with his Incarnation and Baptism, and culminating with his Passion, is to take upon himself our burden, the weight of our sins. By clothing himself with the flesh of our human nature, and taking it through death to Resurrection, Jesus carries man from the condition of death by the side of the road, to the inn, where he cares for him.

The inn, of course, is the Church. Through the sacraments, Jesus brings us into his Church, which is our hospital. There he nourishes and heals (saves) us through the ministry of the “innkeeper,” that is, the clergy and other stewards who dispense the riches of Christ’s life for the salvation of mankind (cf. Lk 12:42). The samaritan gave the inn-keeper two silver coins, representing the rich graces won by Christ’s passion which the Church applies to needs of mankind. The two coins likely represent the body and soul, which are ministered to by the Church in the corporal and spiritual works of mercy. The Church possesses full authority from Christ to act in his name, forgive sins, apply indulgences. Christians help their neighbor in need, whether the needs are physical (sickness, hunger, nakedness) or spiritual (ignorance, sin, afflictions).

At this point the Samaritan leaves, but promises to return and finalize all debts and payments. After establishing man, universally (not just the Jews) in the “Catholic” Church, and entrusting its stewardship to the apostles in his name, Christ ascends back to the Father. In the meantime, the Church acts as man’s caretaker until he returns again in glory to complete the work of salvation.

What Christ has accomplished in this parable, he now enjoins upon his disciples: “As I have done, so you must do” (Jn 13:15). Christians are both the man in need of healing, and the Samaritan who brings healing to others. The Church is both the Body of Christ wounded by sin, and the Body of Christ raised from the dead, anointed with the healing gifts of the Holy Spirit.

When Mother Teresa brought the dying off the sidewalks of Calcutta into her homes, she was responding both to the corporal needs of her neighbor, but also to the deeper spiritual need of the soul. And whereas our corporal works of mercy (hospitals, charities, etc.), great as they may be, do not ultimately solve the problems of mankind, since he will be hungry and sick again tomorrow, the wine and oil of the sacraments do in fact forgive the wounds of sin, and restore health: “He who eats this bread and drinks this wine has eternal life” (cf. Jn 6:41-59).

May our acts of charity toward others be true acts of kindness, that heal both body and soul, and not merely excuses allowing us to continue down the road free of obligation.